|

| The Wanderer in the Exeter Book manuscript |

The Wanderer's reflections on his past life experiences make no mention of overtly Christian concepts, despite the short bit of framing narration after the monologue that provides a devout gloss. Instead, we read of the workings of fate (wyrd) and the relationships of reciprocal gifting in pre-Christian warrior society.

Bruce Mitchell and Fred C. Robinson have remarked that the central figure is of "the heroic age" and "shows no awareness of Christian enlightenment." This is not to argue that the poem preserves a perfect pristine pagan worldview, but merely to suggest that even an ostensibly Christian poem can contain elements of an older belief system.

Discussing Anglo-Saxon verse, Graham Holderness writes:

While the confrontation and synthesis of pagan and Christian elements is necessarily foregrounded in the heroic and devotional poetry of the period, it seems to me that some of the 'deep-set patterns of belief' transmitted from the past into the consciousness of English Christians can also be traced in the elegies, poems regarded as quintessentially expressive of the spirit of the age, yet not formally or explicitly concerned with matters militaristic or theological.I would argue that The Wanderer has elements of both heroic and elegiac poetry. As such, it contains holdovers from a past pagan age presented in a post-conversion package.

My translation of the poem is presented in the text boxes below. Between each section of the translation, my annotation addresses aspects of the poem including:

• Linguistic elements, such as comparison to Old Norse words

• Cultural concepts of Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse society

• Parallels to the Old English Beowulf, probably composed in the 8th century but preserved only in a manuscript of c1000

• Parallels to the Old English Rune Poem, probably composed c1000 but preserved only in a printed edition of 1705; each verse of the Rune Poem explicates the meaning of a specific letter of the futhorc, the Anglo-Saxon runic alphabet

|

| The Old English Rune Poem as it appeared in the first printed edition of 1705 |

• Parallels to Old Norse poems of the Poetic Edda preserved in manuscripts of c1270 and later, with particular emphasis on Hávamál ("Sayings of the High One," i.e. the god Odin, well-known for disguising himself as an old solitary wanderer)

• Influence of the poem on later authors, most notably J.R.R. Tolkien

• Concepts that are of interest to practitioners of Ásatrú and Heathenry, modern religions that seek to reconstruct, reinvent and/or reimagine pagan Germanic religious traditions

Readers who simply want to read the poem can skip over the annotation and move from text box to text box.

Following translators of Old English such as R.D. Fulk and J.R.R. Tolkien, I have rendered all poetry as prose. The full text of The Wanderer in Old English can be found in Bruce Mitchell and Fred C. Robinson’s A Guide to Old English.

Note: All passages quoted from Old English, Old Norse, and German texts in the annotation are my own translations.

The Wanderer

Translated from the Old English and annotated

by Karl E. H. Seigfried

| The solitary one often awaits prosperity for himself, favor of fate, although he, troubled in mind, through sea-ways long had to stir with hands rime-cold sea, to trudge the paths of exile. Fate is fully inexorable! So said the wanderer, mindful of hardships, of wrathful slaughters, with the fall of beloved kinsmen: |

The phrase "through sea-ways long had to stir" (geond lagulāde longe sceolde hrēran) is reminiscent of the Old English Rune Poem verse for the lagu ("sea") rune, which contains related vocabulary: lagulāde/lagu ("sea-ways"/"sea"), longe/langsum ("long"/"longsome"), sceolde/sculun ("had to"/"have to"):

The sea seems longsome to men, if they have to dare in an unsteady ship, and the sea-waves greatly frighten them, and the sea-steed does not heed the bridle.Both poems reflect the difficulty and struggle of the long times at sea necessary for northern travel during this time period.

|

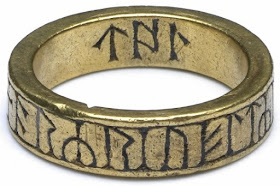

| Lagu rune is the third symbol on the inside of this Anglo-Saxon rune ring (8th-10thC) |

I am not arguing for a direct genetic relationship between the two poems, but rather suggesting that the similarity of vocabulary and imagery shows that they are both part of what Maureen Halsall calls "the shared word-hoard of alliterative formulas... which was the common property of the Germanic-speaking world and which manifests itself in many other poetic contexts outside the rune poems."

The Old English hrīm ("rime," "frost") is used here by The Wanderer's narrator in the compound adjective hrīmceald ("rime-cold"). Old Norse has a parallel hrím and hrímkaldr, but readers of Norse mythology are likely better acquainted with the noun compound hrímþursar ("frost-giants").

The narrator's declaration that "fate is fully inexorable" (wyrd bið full āræd) is well-known to readers of Bernard Cornwell's Saxon Stories (now on BBC Television as The Last Kingdom) as a favorite phrase of the protagonist, Uhtred of Bebbanburg. The statement is also paralleled in line 455 of Beowulf, in which the hero declares "Fate goes as she must" (Gæð ā wyrd swā hīo scel).

This sentiment appears in various forms in several Icelandic sagas, such as the statement by Grímur Ingjaldsson in Vatnsdæla saga that "it is hard to escape fate" (torsótt er að forðast forlögin). The idea is common enough throughout Indo-European literature. In the Sanskrit Rāmāyana, Rama states that "Fate is inevitable" (4.24.6); in the Greek Iliad, Hector says that "no man, I promise, has ever escaped his fate" (6.488).

Both The Wanderer and Beowulf use the word wyrd (translated here as "fate"), a feminine noun cognate with both Old Norse urðr and Modern English weird. In Norse mythology, Urðr is the name of one of the Norns, the mystical women who sit at the Well of Fate (Urðar brunnr) and determine the destinies of men. In Shakespeare's Macbeth, the Norns are paralleled by the Weird Sisters, three prophetic women who gather beneath "lightning and thunder" and discuss meeting "upon the heath."

Direct speech of the Wanderer begins at this point in the poem and lasts until the final lines.

| Often I had to alone lament my care each day before dawn. No one is now alive that I would dare to tell him my heart openly. I as truth know that it is noble custom in a nobleman, that he should bind fast his spirit-enclosure, should keep his hord-coffer closed, think as he will. Nor can a weary spirit withstand fate, nor the troubled mind provide help. |

The Wanderer speaks of the "nobleman" using the word eorl (here in the dative as eorle), which is related to the Old Norse jarl and the Modern English earl. A character named Eorl is mentioned several times in The Lord of the Rings as the first king of Rohan and ancestor of the Rohirrim. His descendants are modeled on Anglo-Saxons (as demonstrated by Christopher Tolkien and Tom Shippey) and are known as Eorlingas (Eorl + ingas). While Old Norse patronymics used the -son suffix to mark a man's father, Old English used -ing to mark the ancestor of a family or a people. Therefore, the Eorlingas are the "people of Eorl."

|

| Reconstruction of Anglo-Saxon helmet found in York that likely belonged to a high-status noble c750-775 |

The word þēaw (here translated as "custom") is used today by some modern followers of Heathen religions to refer to "practices which had proven beneficial or supportive enough of society to have become established standards for behavior or the standard way of doing things" (Eric Wódening, We Are Our Deeds). The Modern English spelling is thew.

Mōd (translated here as "spirit") survives in Modern English as "mood." The Old English word had a much wider range of meanings than does its linguistic descendant. Depending on context, it could mean arrogance, courage, disposition, heart, mind, pride, soul, spirit, or temper. In the compound ofermōd ("over-mood," i.e. "overconfidence," "overweening pride") it is a key term in the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon and is paralleled by the Middle High German übermuot, an important term in the Nibelungenlied's characterization of Prünhilt (the German equivalent of the Icelandic Brynhildr).

| Therefore the glory-eager ones often in their breast-coffers bind sorrowful mind fast, as my spirit, often wretchedly troubled, of ancestral home deprived, far from noble kinsmen, I had to fasten with fetters, since very long ago I covered my gold-friends in darkness of earth, and I wretched from there went winter-desolate over binding waves, hall-sad sought bestower of treasure, where I far or near could find him who in mead-hall might know of mine, or me friendless would console, entertain with joys. |

Ēþel (translated above as "ancestral home") appears here in the dative singular form ēðle. Like mōd, this is a term with a wide range of meanings: ancestral domain, ancestral region, hereditary estate, home, homeland, native land, and territory. The Old Norse parallel óðal covers a similar set of meanings: ancestral property, family homestead, home, inheritance, native place, and patrimony. The Old English Rune Poem verse for the ēþel rune reads:

Ancestral land is exceedingly dear to each man, if he may there in the hall enjoy what is right and fitting in prosperity most often.Like The Wanderer, the Rune Poem makes a connection between "ancestral land" and the pleasures and rewards of life in the hall.

|

| Sae Wylfing, a half-size replica of the Sutton Hoo ship |

When the Wanderer refers to the "mead-hall" (meodoheall, here in the dative form meoduhealle), he uses a term that both Hrothgar and Beowulf use to refer to Heorot, the hall that is the site of Grendel's attacks in the night (lines 484 and 638). The Old Norse equivalent is mjöðrann, which appears in the Eddic poem Atlakviða (verse 9). However, mjöðrann is actually more closely related to the Old English medoærn, a term used by the Beowulf narrator to refer to Heorot (line 69).

Wynn ("joy," here as dative plural wynnum) is the subject of a verse in the Old English Rune Poem:

Joy he enjoys who knows little of woes, pain and sorrow, and for himself has prosperity and bliss and also the abundance of strongholds.This expresses a concept of "joy" that is quite close to that of the Wanderer, centered as it is on contrasting mental states and the prosperity and shared experiences of the hall.

| He knows who knows first-hand how cruel sorrow is as companion to him who for himself has few beloved confidants: path of exile holds him, not at all twisted gold, frozen heart, not at all wealth of earth. He remembers retainers and receiving of treasure, how in youth his gold-friend accustomed him to feasting. All joy has perished! |

The Wanderer's reflection on loss of "joy" (wyn) continues with more parallels to the verse from the Runic Poem quoted above. Shared vocabulary between this section of The Wanderer and the wynn verse includes cunnað/can ("knows"), sorg/sorge ("sorrow"), blæd ("wealth," "prosperity"), and wyn ("joy").

|

| "Odin the Wanderer" (1886) by Georg von Rosen |

The lament of the man who "has few beloved confidants" (lyt hafað lēofra geholena) is echoed by the words of Odin in the Old Norse Hávamál ("Sayings of the High One," verse 50):

The young fir-tree withers, that which stands in an unsheltered place; neither bark nor needle shelters it. Such is the man whom no man loves – how should he live long?Although the imagery is different, the two poems share an underlying concept of community.

The Wanderer's emphasis on "receiving of treasure" (sincþegu, here as accusative sincþege) from the "gold-friend" (goldwine) underscores the importance of reciprocity and reciprocal gifting between the lord (a Modern English word descended from the Old English hlāfweard > hlāford = "loaf-ward," "bread-keeper") and his dependents. The leader was responsible for providing food, shelter, and treasure for his retainers in exchange for their loyal service. This relationship is also at the heart of the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon.

In Hávamál, Odin mentions this relationship of reciprocal gifting (verse 42):

To his friend a man must be a friend and repay gift with gift.The Wanderer makes a direct connection between loss of friends and the loss of gifting. Odin also seems to warn against the very situation in which the Wanderer finds himself (Hávamál, verse 41):

Those who exchange and those who give again are friends to each other the longest – if that continues to go well!Clearly, things haven't gone well for the Wanderer.

| Therefore knows he who must do without counsels of his beloved friend-lord for a long time: when sorrow and sleep at the same time together often bind the wretched solitary one, it seems to him in his mind that he embraces and kisses his liege lord and on his knee lays hands and head, as he at times before in days gone by enjoyed the giving-seat. Then the friendless man awakes afterwards, sees fallow waves before him, sea-birds bathe, feathers spread, rime and snow driving mingled with hail. |

|

| Hrothgar doesn't look like he's in a giving mood in this illustration by Randy Grochoske |

The "giving-seat" (giefstōl, here as genitive giefstōlas) from which the lord rewards his retainers seems equivalent to the Old Norse "high-seat" (hásæti, hástóll, öndugi, öndvegi) that is mentioned so often in the Eddas and sagas.

Hæl ("hail," here as dative hagle) is featured in one of the verses in the Old English Rune Poem:

Hail is the whitest of grains; it whirls from heaven's sky, storms of wind toss it; afterwards it is made into water.Perhaps a bit more prosaic than the other verses quoted above, but there it is.

| Then wounds of the heart are the heavier, sorely longing for the beloved. Sorrow is renewed. Whenever remembrance of kinsmen pervades his mind, he joyfully greets, eagerly examines companions of men; they often swim away. Spirit of floating ones does not bring there many familiar sayings. Care is renewed for him who must very often send weary heart over binding of waves. Therefore I am not able to think throughout this world why my spirit does not grow dark, when I fully ponder life of noblemen, how they quickly abandoned hall, brave young retainers. So this middle-earth each of all days declines and falls; therefore a man can not become wise, before he has a portion of winters in the kingdom of the world. |

"Middle-earth" (middangeard, "middle-yard") is the Old English equivalent of the Old Norse miðgarðr (also meaning "middle-yard"). The former is the source for Tolkien's "Middle-earth," the latter for "Midgard" in Modern English translations, retellings, and reimaginings of Norse mythology.

|

| Hávamál illustration (1908) by W.G. Collingwood |

The emphasis on wisdom and experience is reminiscent of sections of the Old Norse Hávamál in which Odin speaks of the "unwise man" (ósnotr maðr, verse 26):

An unwise man thinks he knows all, if he has for himself a corner to stay in.That is to say, the fool who never leaves home considers himself wise – an observation that still holds true in this age of internet trolls.

We still use the Old English word winter (here as genitive plural wintra). Both the Anglo-Saxons and the Norsemen measured a person's age by winters instead of years. Beowulf rules his kingdom for "fifty winters" (fiftig wintra, line 2209) before the dragon attacks; Helgi of the Völsunga saga goes off to war when he is "fifteen winters old" (fimmtán vetra gamall, chapter 8).

| The wise man must be patient, must not be too hot-hearted nor too hasty with words, nor too weak a warrior nor too reckless, nor too afraid nor too obsequious, nor too wealth-greedy nor never of boasting too eager, before he clearly has knowledge. A warrior must await, whenever he speaks a vow, until stout-hearted he knows clearly whither thought of his heart will turn. A wise man must understand how terrifying it will be, when the riches of all this world stand deserted, as now in various places throughout this middle-earth walls stand wind-blown, rime-covered, the buildings snow-swept. |

The qualities given here of "the wise man" (wita) parallel those discussed by Odin in Hávamál. Both the Wanderer and Odin place an emphasis on moderation (Old English metgung, Old Norse hóf). In Viking Age Iceland, Jesse Byock connects this idea to the reciprocity discussed above: "Success in maintaining reciprocal agreements... required conformity to a standard of moderation, termed hóf. An individual who observed this standard was called a hófsmaðr, a person of justice and temperance." Maybe today's Heathens who adhere to the "Nine Noble Virtues" should consider adding "moderation" to the list. In today's world of overheated online rhetoric, a little restraint couldn't hurt.

|

| Cattle in the winter snow of Exter, England |

The Old English word feoh appears here joined to the word gīfre ("greedy") to form the compound adjective feohgīfre ("wealth-greedy"). The Old English feoh and Old Norse fé have two ranges of meaning: (1) cattle, livestock and (2) property, wealth. In his Dictionary of English Etymology, Hensleigh Wedgwood writes, "The importance of cattle in a simple state of society early caused an intimate connection between the notion of cattle and of money or wealth." Related words in Modern English include fee, fief, and feudal.

Feoh is the subject of the first verse of the Old English Rune Poem:

Wealth is a consolation to all people; though each man must deal it freely, if he wishes to obtain glory before the lord.As in The Wanderer, the importance of reciprocal gifting is underscored.

Beorn (here translated as "warrior") is a word that only appears in Old English poetry (i.e., not in prose works) and is used to mean man, warrior, prince, nobleman, or chief. Both beorn and bera ("bear") are cognate with the Old Norse björn ("bear"), but the meaning of björn seems to have evolved from the animal to the human. Tolkien tapped into the transformation of the word when he created The Hobbit's Beorn, a mysterious character who shifts between bear and human form.

The Wanderer stresses the gravity of making a vow (bēot). Mitchell and Robinson write that "the speaker is warning against rash vows... uttered in public, since a man would earn contempt if he failed to carry out what he boasted he would do." This view of vows is held today by many modern practitioners of Heathenry, and the seriousness of making oaths is discussed at length by contemporary Heathen authors such as Patricia M. Lafayllve, Diana L. Paxson, and Eric Wódening.

Edoras (translated here as "buildings") is the plural form of the noun edor ("place enclosed by a fence," "dwelling," "house"). Again connecting the Rohirrim to the Anglo-Saxons, Tolkien gives the name Edoras to their hilltop fortress in The Lord of the Rings.

| The wine-halls decay, rulers lie deprived of joy, troop of seasoned retainers has all perished, proud by the wall. War took some away, carried into the way forth, a bird bore away a certain one over the high sea, a gray wolf shared a certain one with death, a sad-faced nobleman hid a certain one in an earth-grave. |

The imagery of animals preying on the battle-dead should be familiar to readers of the Norse myths and sagas, which feature ravens and wolves as the battlefield-haunting creatures of Odin. The Wanderer's statement that "a gray wolf shared a certain one with death" (sumne se hāra wulf dēaðe gedælde) brings to mind Odin's rationale for gathering heroes to Valhalla in the Old Norse poem Eiríksmál: "the gray wolf gazes at the homes of the gods" (sér ulfr hinn hösvi á sjöt goða).

| So the creator of men laid waste this dwelling place until, devoid of the revelry of the population, the ancient works of giants stood idle. |

"The ancient works of giants" (eald enta geweorc) here refers to buildings, but a similar phrase is used in Beowulf to describe a sword when the hero finds an oversized weapon during his battle with Grendel's mother (line 1557):

Then he saw among the war-gear a victory-fortunate blade, an ancient sword made by giants (ealdsweord eotenisc) strong in edges.In Old English, ent (here in genitive plural enta) and eoten (here in the adjective form eotenisc) both mean "giant." The latter word is related to the Old Norse jötunn ("giant"), a word that may derive from eta ("to eat"). The sense of the enemies of the gods having enormous appetites is also present in the Sanskrit texts of India, in which the rakshasas are defined by their monstrous hunger. Like the jötnar (plural of jötunn) of Norse myth, rakshasas appear in Indian texts as both terrifying ogres and beautiful women.

|

| Sword with Anglo-Saxon silver inlay found in a grave in Heggestrøa, Norway |

The phrase "works of giants" (enta geweorc) also appears in several other Old English poems: Andreas, Beowulf, Maxims II, and The Ruin. In his Mittelerde: Tolkien und die germanische Mythologie ("Middle-earth: Tolkien and Germanic Mythology"), Rudolf Simek explains why the Old English poems credit "giants" with the construction of ancient structures: "To these old giants, people in the early middle ages attributed the creation of the prehistoric stone-monuments and also the Roman streets and buildings, which were still visible then in great ruins." Earl R. Anderson writes of a "theme of an awed regard for Roman ruins" in Old English poetry: "These ancient stone structures have endured the ravages of time, wind and weather, and are admired [by the Anglo-Saxons] in part because of their antiquity."

Tolkien credits the creation of the Ents in his own mythology to this line of The Wanderer, writing to W. H. Auden (letter 163) that his giant figures of the forest "are composed of philology, literature, and life."

| He who then wisely considered this foundation deeply meditates on this dark life, wise in spirit, often remembers large number of slaughters far, and utters these words: Where has the horse gone? Where has the young man gone? Where has the treasure-giver gone? Where have the seats of the feasts gone? Where are the hall-joys? Alas, bright goblet! Alas mail-warrior! Alas, glory of the prince! How that time departed, grew dark under helm of night, as if it never was. A wall wondrously high, decorated with serpent shapes, stands now in the track of the beloved troop of seasoned retainers. Powers of ashen spears have taken noblemen away, weapons slaughter-greedy, fate the glorious, and storms batter these stone cliffs, falling snowstorm binds the earth, tumult of winter, when dark it comes, night-shadow darkens, sends from the north fierce hailstorm to the warriors in hostility. |

The Wanderer uses the word frōd ("wise") in the phrase frōd in ferðe ("wise in spirit"). In J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, Tom Shippey points out that Frodo is "the one name out of all the prominent hobbit characters in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings which Tolkien does not mention or discuss." Given that "wise in spirit" seems such an apt description of the Ring-bearer, perhaps this half-line from the poem Tolkien knew so well played some part in his naming of Frodo.

|

| Warriors drink in the hall Beowulf illustration (1939) by Lynd Ward |

The Wanderer again refers to reciprocal gifting when he mentions the "treasure-giver" (māþþumgyfa). Of course, gyfa ("giver") is related to gyfan ("to give") and gyfu ("gift"), the latter of which is the subject of a verse in the Rune Poem:

The gift of men is honor and praise, support and respect; and help and substance for each wanderer who is without other.This reminds us that the Wanderer is not bemoaning the simple loss of material things, but of the relationships and cementing of status that the giving and receiving of gifts represents.

The Old English symbel ("feast," here in the genitive plural symbla) is parallel to the Old Norse sumbl. In The Well and the Tree: World and Time in Early Germanic Culture, Paul C. Bauschatz presents a detailed analysis of usage of both terms in the literature of the two languages, arguing that Beowulf and several poems from the Poetic Edda provide evidence for a Germanic ritual based on drinking of an alcoholic beverage, making of speeches, and giving of gifts.

Bauschatz's theories have been widely influential on modern Heathen practice. So far, every book that I have found published by a Heathen author that discusses the contemporary version of the symbl or sumbl ritual cites his work. Our Troth, a two-volume religious guide by the Troth (an American Heathen organization), states that nearly all practitioners "who have written or spoken on the meaning of the sumbel in latter years have drawn their understanding of the rite from this text."

The section of The Wanderer beginning "Where has the horse gone?" should be familiar to readers of The Lord of the Rings. In The Two Towers, Aragorn recites the "Lament for the Rohirrim":

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?At it's opening, Tolkien's poem is quite close to the lament of the Wanderer. Although the language quickly diverges, the spirit, mood, and imagery remain very similar.

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the hand on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing?

They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow;

The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow.

Who shall gather the smoke of the dead wood burning,

Or behold the flowing years from the Sea returning?

When Aragorn performs the poem for his companions, he is himself a wanderer standing next to "the great barrows where the sires of Théoden sleep." The character name Théoden is from the Old English þēoden ("prince, lord") which appears in this passage of The Wanderer as the genitive þēodnes in the phrase Ēala þēodnes þrym ("Alas, glory of the prince"). In Peter Jackson's film of The Two Towers, three non-contiguous lines of Aragorn's lament are transferred to Théoden, with editorial "improvements" of language by the movie's producers.

| All is fraught with hardship in the kingdom of earth, the creation of the fates changes the world under the heavens.

Here wealth is temporary, here a friend is temporary, here oneself is temporary, here a kinsman is temporary; all this foundation of the earth will become worthless! |

The second sentence here is quite close to a popular passage from the Old Norse Hávamál. The Old English uses the word feoh in its opening phrase, and the Old Norse uses fé at the start. As discussed above, both words can mean either "wealth" or "cattle." In the words of the Wanderer, the meaning is generally accepted to be "wealth" or "property"; in the words of Odin, it is clearly "cattle." Verse 76 of Hávamál states:

Cattle die, kinsmen die, the self dies the same, but the glory of reputation never dies for the one who gets himself a good one.Two pairs of the Old English and Old Norse words are related: feoh/fé ("wealth"/"cattle"), frēond/frændr ("friend"/"kinsmen"). The parallel nature of the two verses is obvious. However, the worldview expressed by the two endings are quite different.

|

| "December" by Hans Thoma (1839-1924) |

The Old English poem responds to the realization of the transitory nature of life by denigrating the worth of the world itself, and suggesting that the afterlife is all that truly matters (as made explicit in the narrator's Christian conclusion below). The Old Norse poem replies to the same situation with an insistence that deeds in the world are what matter, that the only immortality is in the reputation we leave behind. One attitude is world-denying, the other world-affirming.

Direct speech of the Wanderer ends at this point in the poem.

| So said the one wise in spirit, sat himself apart in secret meditation. Good is he who his maintains his faith, nor ought a man ever his grief too quickly of his breast make known, unless he, the nobleman, before then knows how to bring about amends with courage. Well is it for that one who seeks mercy for himself, consolation from the Father in the heavens, where for us all the fastness stands. |

The narrator returns and states that the Wanderer sat alone "in secret meditation" (æt rūne). The word rūn (here as dative rūne) refers to the secret and mysterious nature of the act, not to the runic symbols. What we would today call a rune was known in Old English as a rūnstæf ("runic letter").

Trēow (as accusative trēowe) is here translated as "faith," but also means "trust" and "loyalty." It is related to the Old Norse trú ("faith," "belief") which is used today as part of the Modern Icelandic term for the contemporary Heathen religion Ásatrú ("Æsir Faith," belief in the Norse gods).

The poem ends with the narrator's statement on Christian "mercy" (ār, as accusative āre) and "consolation" (frōfor, as accusative frōfre). However, the final image is that of a "fastness" (fæstnung) "in the heavens" (on heofonum), which fits well with the Wanderer's nostalgia for bygone days of drinking in the stronghold of his lord.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Earl R. "The uncarpentered world of Old English poetry." Anglo-Saxon England 20 (1991): 65-80.

Bauschatz, Paul C. The Well and the Tree: World and Time in Early Germanic Culture. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1982.

Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995.

Dronke, Ursula, ed. The Poetic Edda, Volume III: Mythological Poems II. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Eiríksmál. Heimskringla website, heimskringla.no/wiki/Eir%C3%ADksm%C3%A1l.

Fulk, R.D., Robert E. Bjork, and John D. Niles, eds. Klaeber's Beowulf and the Fight and Finnsburg. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008.

Gundarsson, Kveldúf, ed. Our Troth, Volume Two: Living the Troth. BookSurge Publishing, 2007.

Halsall, Marueen. The Old English Rune Poem: a critical edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981.

Holderness, Graham. "From Exile to Pilgrim: Christian and Pagan Values in Anglo-Saxon Elegiac Verse." In English Literature, Theology and the Curriculum, 63-84. Edited by Liam Gearon. London: Cassell, 1999.

Homer. The Iliad. Translated by Stephen Mitchell. New York: Free Press, 2011.

Larson, Laurence M. "The Household of the Norwegian Kings in the Thirteenth Century." The American Historical Review XIII (October 1907 – July 1908), 459-479.

Mitchell, Bruce and Fred C. Robinson. A Guide to Old English. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Rāmayāna, Book Four: Kiskindhā. Translated by Rosalind Lefeber. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Shippey, T.A. J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Simek, Rudolf. Mittelerde: Tolkien und die germanische Mythologie. Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2005.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings, Part Two: The Two Towers. New York: Ballantine Books, 1981.

Völsunga saga. Heimskringla website, heimskringla.no/wiki/V%C3%B6lsunga_saga.

Wódening, Eric. We Are Our Deeds: The Elder Heathenry, Its Ethic and Thew. Baltimore: White Marsh Press, 2011.

This modern English translation and annotation

© 2016 by Karl E. H. Seigfried

Click here for more free full text online translations from the Old English.

No comments:

Post a Comment